An Interview With Mary Shelley

It was an honour and an all-round wonderful experience to be asked to judge the Dead Romantic Interviews writing competition for Edge Hill University’s Romantic Lives Conference. There were a lot of terrific entries and it was difficult to choose a winner. You can read the winning entries here.

To kick-start the competition, I wrote my own interview with… of course… Mary Shelley herself. Read it at your peril:

It is on a dreary night of November that I behold the accomplishment of my toils. A few weeks earlier, a scholar wrote to ask me to interview Mary Shelley, my long-dead literary heroine, a puzzling invitation to be sure. Who would have thought that the quest for answers would see me robbing a grave in Bournemouth? Publish or perish indeed! In a lonely cemetery near the beach, I dug up Shelley’s bones and carried them home for the next grim phase of the task.

On the top floor of my house, in a dimly lit cell, I assemble my workshop of filthy creation, collecting the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the insensible flesh that lies in two Sainsbury’s bags by my feet. In the early hours, by the glimmer of the late night TV creature feature, I wait for movement to agitate Mary’s limbs. Outside the window, lightning shreds the sky, once, twice. The walls of the room began to tremble. In panic, I clutch at the wires of my machine, fearing that the storm will break apart my work. The third bolt of lightning peals like a death’s knell, turning the air around me white.

The next time I open my eyes, I see a square house perched on the shore of a lake. The sky still shudders with the storm. The trees around me are tall, the moon bright. A few paces from where I stand, the door of the white, pillared house gapes open. I run through and the wind slams it behind me. Orange firelight beckons me forward and I find myself in a grand, oak-paneled drawing room strung with chandeliers. In an armchair by the sputtering flames, a young girl, perhaps in her late teens, leans over a notepad, writing furiously, her long hair curling over the blanket draped across her shoulders.

MS: Cloris, is that you?

Stunned beyond speech, I shake my head. The girl looks up and regards my dripping hair and drenched clothes with mild concern.

MS: Pray, are you the new maidservant travelled from the village? Your face is unfamiliar to me, your clothes too. You must sit by the fire and dry yourself awhile, else you will catch your death.

The gleam in her dark eyes, which I recognise from portraits, the pale skin, the quaint manner of speech… I feel with sudden certainty that this is Mary Shelley and the house around us, Byron’s rented summer accommodation, Villa Diodati on the shore of Lake Geneva. The year is 1816 and we are in the depths of winter. My machine has not reanimated Mary as I’d hoped, but here nonetheless is my chance for an interview. As subtly as I can, I pull out my iPhone and open the Notes app.

KH: Erm… Mistress Godwin, pray what do you work on at such a late hour?

MS: [sighs] Something, I hope, to rival the endeavours of the gentlemen.

KH: Endeavours… such as… writing?

MS: [nods a little impatiently] In this frightful cold, we have had nothing to amuse ourselves with but German ghost stories rendered into French from the Fantasmagoriana. A few nights past, we lounged about the fire reading them aloud to each other, Lord Byron and Master Polidori… and of course, my dear Percy. Moments before our conversation, they were running about unclothed, plunging bare flesh into the freezing waters of the lake—

KH: Oh, so Ken Russell wasn’t too far off-base after all…

MS: Of whom do you speak?

KH: Oh, never mind. Please carry on.

MS: [looks puzzled] Your manner of speech is strange, new maidservant who is not Cloris, but I will confess that many diverting ideas passed among us that evening. The muse alighted in all of us and it was decided we should strive to see who might compose the most alarming work, something that would shock the rest extremely. Alas, days have passed, and I have naught but scraps and babble here. “Have you thought anything good?” the gentlemen ask me each morning, and each morning I am forced to reply with a mortifying negative!

Mary sighs desolately and lays down her pen on the arm of the chair, spattering dark pools of ink on the blood red fabric. For a long while after that, she stares into the fire in silence, running her pale fingers through her hair until it is wild. An hour before, I had burned with the hope of speaking to Mary at the end of her career and asking the many questions about her life’s work that plagued me – how a young girl came to think of, and to dilate upon, so very hideous an idea. Now, here she is, a girl still, poised to step out from childhood towards her greatest creation. I am torn between a desire to encourage her and a fear that disrupting her reverie could change the course of literary history. Eventually I settle on what seems the safest path.

KH: Had any good dreams lately?

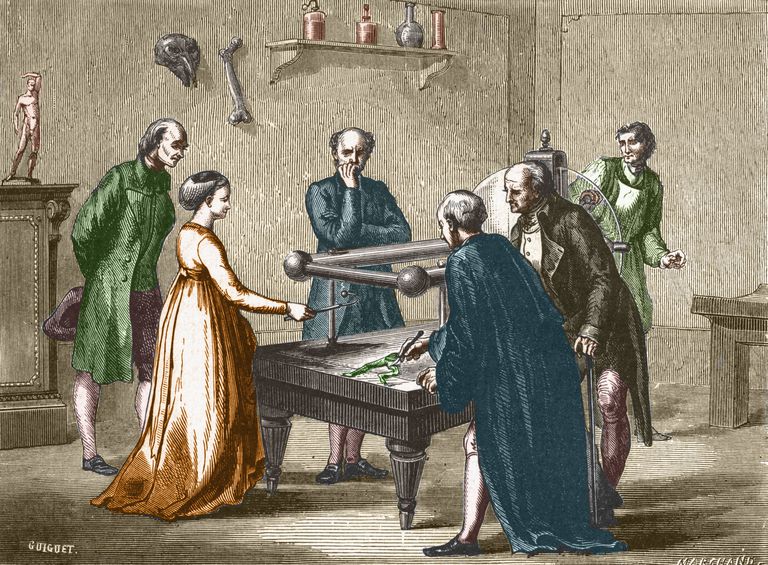

MS: [shaking herself from her trance] Only horrid ones. Black nightmares rather than dreams. The fault is Polidori’s! The night of the Fantasmagoria, we spoke of practising galvanism, whether we might between all of us revive dead bones. Of course the wretch could not resist raising the matter of the occult and terrorizing us all with tales of Frankenstein Castle, where an alchemist once engaged in dreadful experiments. Ever since, my fancy has been possessed with thoughts of reanimated flesh. I retire each night to the grim terrors of a waking dream in which a scientist creates life only to be horrified by his work.

KH: When you say “doctor” you mean a sort of pale student of unhallowed arts kind of thing? Maybe kneeling beside something he’s put together?

MS: Yes indeed, I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion…

KH: Okay, so you should definitely jot that down. That’s sounding perfect right there. I mean to say, what terrified you will terrify others. You need only describe the spectre which has haunted your midnight pillow.

MS: [writes furiously, only to crumple the paper up and toss it in the fire a moment later] The matter is quite hopeless, not-Cloris! Byron has written his piece already, albeit not a thing of length, and Polidori is composing a novel, indeed. Perhaps it is true what men say and my woman’s mind is too weak for the task.

KH: Mary! What would your mother say? She worked so hard to pioneer feminism.

MS: Ah, dear Mama. I saw her but a day of my life though I have laid oft upon her grave and wept bitterly. Indeed, I once near half read A Vindication of the Rights of Woman before Papa withdrew it from my hands and put in its place the second volume of Caleb Williams, which he told us he considered a weightier endeavour.

KH: [impatient] Well, you know what they say: “A slavish bondage to parents cramps every faculty of the mind.” So how about you just humor me and write it down again, you know, what you were saying before about Victor Frankenstein, the Creature, the unhallowed arts. That stuff is GOLD, I promise you. In less than a hundred years time, those characters will tower fifty feet high on the silver screen.

MS: [beginning on a new sheet of paper] Frankenstein – the name of the castle! It has a ring to it, to be sure. I have been considering ‘The Modern Prometheus’ as a title for my work, but ‘Frankenstein’, indeed, has some merit.

The clock on the mantle chimes three, startling me. Time is flying past and still I have not discovered any of the answers I need.

KH: [leaning forward] Mary, I must understand. What was the spark of your inspiration? I know about the night around the fire, your knowledge of galvanism, your sister’s tragic death … But you seem like such a nice girl. Wherein does the darkness lie? Or are those detractors onto something when they say that after all it was Percy who did the real work?

The clock chimes a final note. Mary’s delicate face turns pale, the shadows circling her eyes darkening almost imperceptibly in the candlelight. With trembling hands, she rests her paper and quill on the floor beside her chair.

MS: Please, Cloris, stop your questions, I beg of you. I understand not your talk of fiction. I am composing something, yes, or attempting to, but I am no fiction writer. I have only ever been a memoirist of sorts… I have only ever told… the truth.

KH: [startled] The truth?

From somewhere behind me, I hear the heavy thud of footsteps descending the stairs. The oak creaks so loudly, I consider the possibility that Byron has left off his diet of crackers and developed a heavier gait than his portraits would imply.

MS: Oh Cloris, when I said that Polidori and the others conversed about the possibility of reanimating dead flesh with galvanism, I did not tell you all.

KH: [teeth chattering] What are you trying to say?

MS: [turning yet paler] I have no words that would be sufficient to describe the results of all the toying we have done with nature this dreary summer, the celestial powers we have harnessed… the demons we have unleashed, or the monsters this mad science has made of all of us. Look behind you!

I turn to see the figure framed by the great, mullioned windows; lightning strikes at that moment, revealing his gigantic stature. The man standing in the drawing room with us is about eight feet in height and proportionably large.

FM: Parts, Mother. We are sorely in need of them.

The Creature approaches, his translucent yellow skin pulled so tight that it barely disguises the workings of the arteries and muscles beneath, his watery eyes aglow in the gloom, black lips peeling back to reveal a gleaming rictus-grin.

FM: Mother… dear Mother. You have a visitor, I see.

MS: [shrinking back] Do not touch me, foul creature.

FM: [a little hurt] Do I shame you, Mother?

Suddenly I understand what Mary meant by a ‘memoir’. Frankenstein is no fiction, but a barely veiled account of the truth, which some say is stranger than fiction, anyway. Thunder growls. The Creature turns his head, transfixed by the approach of a second figure, slighter than himself, but no less misshapen. She shuffles forward, her one hand, stitched crookedly at the wrist, fumbling for his – the Bride, as yet unfinished by the looks of things.

FM: She needs a second arm, Mother, and very tall hair, which for some reason I admire. I asked you to fashion me a wife from that maidservant I killed, for companionship. I drew a picture for you, Mother, with labels.

BF: [childlike] Sew my rest of me, Mama.

MS: [shuddering] And from whence do you propose we furnish these items?

In the gloaming, the creatures’ yellow skin glows with the sallow waxiness of tapers. Slowly their red eyes turn towards me.

KH: [gathering up things] I… I really must be on my way.

MS: [turning a questioning gaze on me] Pray, Cloris, sit and continue our discourse. Who sent you to the Villa Diodati? Tell me truly.

KH: [sitting nervously] Well, Mary… you’re a literary heroine of mine, someone whose books I’ve read dozens of times.

MS: [suspicious] And you wish to compose your own book?

KH: I… well… I have written a book of my own, about the maidservant who was turned into the Bride of Frankenstein, as a matter of fact. I drew my inspiration from you, and that’s why I came to interview you tonight, I guess.

MS: [coldly] You have stolen my ideas, you say?

KH: Umm… in a manner of speaking, but by the time I publish, dear Mary, you will have been dead many years. Your work will be long out of copyright. It’s quite an established tradition in my day. Lots of authors do it!

MS: So, I will be dead in your time and my work will be anyone’s for the taking, to do with as they please? It seems no accident that you are here.

KH: Yes, I mean, no… I mean it’s no accident, I suppose. I built the machine you describe in your book to reanimate you. Only instead of reviving your bones as I had intended, I found myself here, in your time—

MS: You are as poor a scientist as you are an interviewer, then.

KH: I had H G Wells’ The Time Machine open at the same time. I must have got some passages confused.

MS: I do not know this Master Wells, but I presume you intend to steal his work also? I have peered at the glowing device you are tapping away on at this very moment, fiend, and it shows nothing but a tapestry of my own words taken from me, a shallow pastiche. You, ma’am, are a thief!

KH: [panicking] Not a thief, so much as… I repurposed a few things I liked… not so different, perhaps, from the way you repurposed your servants into these… lovely creations of yours.

MS: From those moments of invention, I did derive a gratification of a truly Olympian style.

The Creatures edge closer, ever closer to where I sit, trying hard not to reveal my growing fear. The Bride’s festering right foot makes an unmistakable scratching sound as it trails the floor. I can see she’s going to need a new one of those, too. Without really meaning to, I tuck my own feet under my chair. I went in search of Mary Shelley’s dark side and now, I fear, I have discovered it.

MS: [a sly smile stealing across her pale cheeks] You know, if you would like to see where my inspiration really took hold, where the sparks of Prometheus are truly made, I could show you upstairs… to our laboratory. I think you will discover many machines to divert you there. I think you will find that I am a woman of parts indeed [laughs] and soon you might follow in my footsteps.

FM: Come with us, Cloris. You are very like the servant I killed in size of limb and every dimension. Miserable wretch though I am, that makes me glad.

BF: [reaching out her badly stitched hand] Sister, come play.